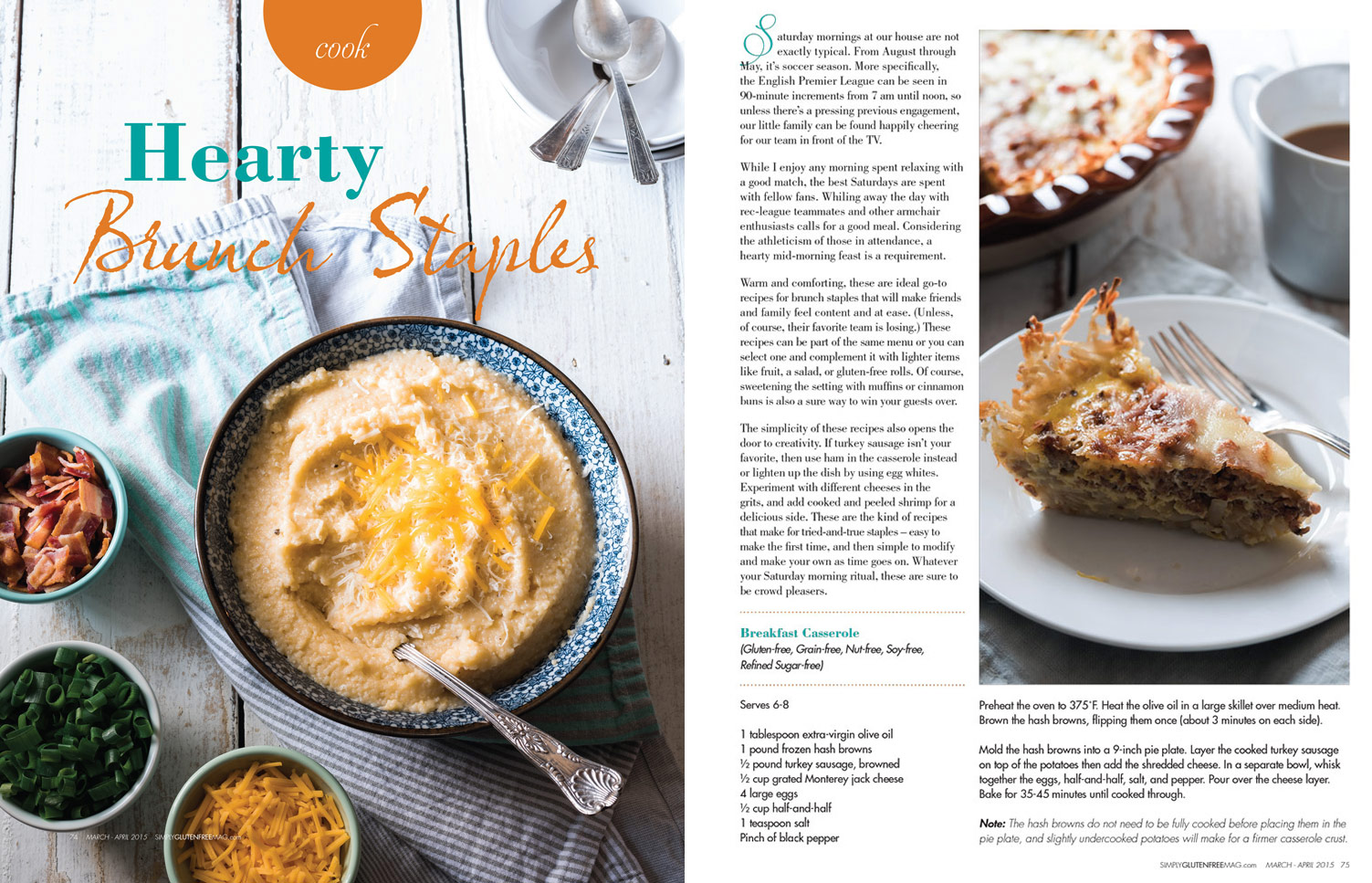

About two months ago I started a new job as the assistant editor of fresh style magazine. As a creative lifestyle magazine, it that has me investing in a side of my talents I never thought had professional potential. I spend most of my days writing and managing our website, and about once a week I head home to create a new handmade project or test a recipe. During my second week on the job, I even created my own recipe for Gluten-Free Brazilian Carrot Cake Cupcakes. What amazes me most is that on a daily basis, I am now working on the kinds of things most people try to fit into their spare time as a hobby.

The move to this job, though, even the willingness to consider a 9-to-5 position in an office was a rather intense process. Because I want this blog to be about processes and how things come into being, I thought it would be a good place to reflect on how this job became something new and exciting for me. It has caused me to question how I define success, and what it takes to find work that you love.

Seven Years in the Making

When I started college, I wanted to be a writer. Since at least middle school, that was my dream, and by 18 years old, I imagined a career in journalism where I would publish fiction on the side. The entire reason I started studying history was because during an experiential learning course at C-SPAN's headquarters in DC, the cable news channel's founder Brian Lamb told me that if I wanted to be a journalist, I needed to know my history. After my first history class, I was hooked and eventually decided to forego journalism for a career in academia instead. I remember thinking that with the combination of research, writing, and teaching, being a professor was my actual ideal job. After all, I would still be writing, even if I wasn’t a “writer” per se. It seemed like a way to write without the risks and potential rejection of pursuing writing full time.

I didn't immediately jump into graduate school, though. Following some sage advice from my advisor in the history department, I waited and got a full-time job instead. I spent two years working in the PR and marketing office at the University of Denver, my alma mater. I had been a work study and intern in the office throughout undergrad, so it was a natural transition. While it wasn't bad work, it didn't hold my attention in a way that made me want to stay long term. After about a six months, I knew I wanted to return to school and eventually join the ranks of academia.

More than six years of graduate school in the history PhD program at Rutgers University ensued. Looking back, I enjoyed probably 90% of my experience as graduate student. I loved discussing ideas and thinking through the complex ways that change takes place. I felt at home within those hallowed hall of higher learning, and wanted to stay there. Not that the experience was without its points of frustration. In particular, the apparent lack of substantial connection to the broader public was difficult for me to understand. Especially the idea of working for years on a research project that few people would read or find interesting made me wonder if there might be some other track, or a way that I might still make a bigger impact while remaining happily within the security of a tenured job.

My real problems in academia came at the end of grad school, when I confronted the dire inequalities of academic employment—something for which I had little real preparation. There have been numerous blog posts, online and print newspaper articles, and other studies on the problems that plague the job market in higher education. I will not rehash them here. Suffice to say, despite my very best efforts (which included learning and doing research in Arabic) I became one of the hardworking, diligent and committed PhDs unable to find work beyond adjunct teaching. As the story goes, there were elements of my personal life that arguably got in the way of my academic success. My husband Stephen has a successful photography business here in Birmingham, so moving from one short term position to another as a Visiting Professor meant we would have to live apart—an option we ruled out at the start of our marriage. I also needed a job in a relatively large city, so that Stephen could still find work. Those priorities made finding a job all the harder, so I started adjunct teaching, first at Birmingham-Southern College and then at the University of Alabama. While I loved both schools, the students there, and teaching in general, after a year of working full-time hours for less than part-time pay, I simply couldn't face another semester of scrambling for classes, pouring my energy into lecture writing, and grading on the weekends, only to see the hope of a "real job" continue to feel further and further away. Perhaps it’s that sense of artifice—that working as an adjunct isn’t substantial, significant or real—that makes it such a humiliating line of work. That and the dismal pay.

Defining success

Considering a job outside of academia, though, required a difficult shift in my mentality. Surprisingly, I found my training in history proved especially valuable on a personal level when it came to deciding to apply for a different kind of job. For my dissertation, I studied people who descended from the survivors of the Spanish Inquisition, who escaped massacre at the hands of the Ottomans on the Greeks Isle of Chios, and who fled Nazi persecution—this mixture of diasporic peoples and their progeny all eventually ended up in an especially multinational neighborhood south of Cairo, called Ma'adi. While their stories taught me about the global flows of economic, social, and cultural influences, they also taught me about resilience.

Most of the people I studied suffered incredible losses—some personal, some financial, others a combination of tragedies—yet they adapted and adjusted their lives, capitalizing on the unexpected opportunities that opened up amid their struggles. Ultimately, many of them turned the experience of survival into a method for making a new life. Learning about their willingness to adjust has since proved to be the most rewarding element to come from my years of research and writing. Their stories inspired me to consider looking beyond the narrow goal of a tenure-track job. Just acknowledging that it was narrow provided a sense of freedom. Rather than lose hope and grow frustrated and angry, why not look at the other things I’m capable of doing and find other options? Why not define my success, rather than letting my supposed career track define it for me?

PhD programs groom you for tenure-track work. Thankfully, more professional associations, including the American Historical Association, are now encouraging graduate programs and students to broaden their horizons and see graduate work as the accrual of a useful set of skills rather than one particular kind of job. Most PhD students, however, go to grad school after already accepting that only attaining a tenure-track job will mean they have achieved success. Such stringency can become a strange religion, where you worship ideas, feed off the the competition over claiming them, and find salvation in the security of tenure. It was heartbreaking to have my seeming redemption withheld after so much work. Realizing there was more to me than that one line of work, however, transformed how I saw the opportunities around me.

New old dream

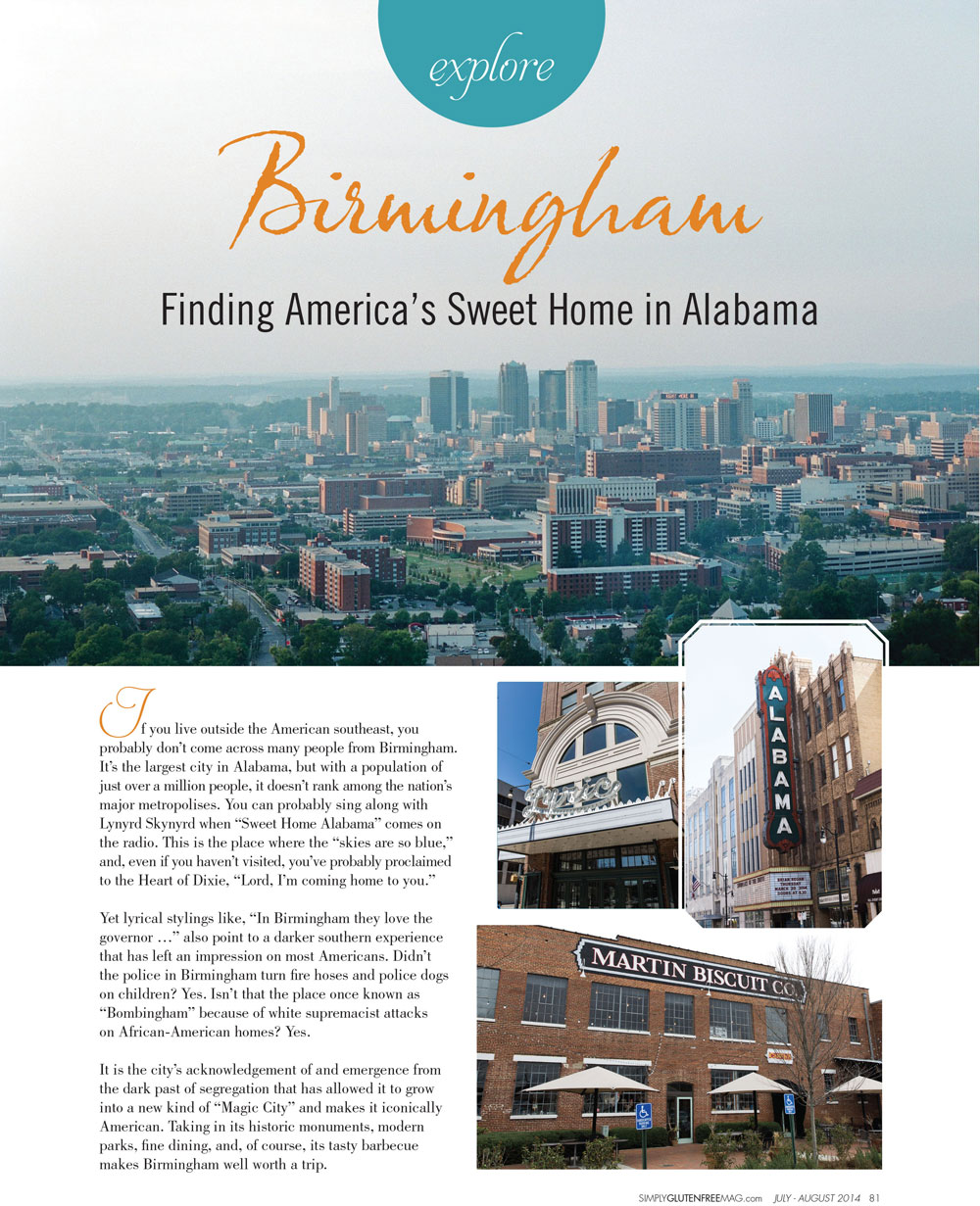

Now that I'm writing all the time, researching, and doing hands-on problem solving everyday, I find I’m using the skills I acquired in graduate school in a more hands-on way than I would have were I prepping to teach yet another semester of Western Civ. I'm also doing work more akin to what I had always wanted to do when I started college. I am a writer, and I am hopeful about the doors that will continue to open up while I pursue a childhood dream I once dismissed as impractical. Who would have thought a move to Birmingham, AL would open up these doors in the first place?

A number of unexpected benefits came from switching lines of work. My dissertation research has proved personally beneficial and so much more than a project meant only for the ivory tower. Beyond that, I now appreciate what it means to set my own goals and priorities, rather than having a particular institution or career path set them for me. Each new endeavor requires a certain amount of sacrifice and adaptability. Now I see the importance of defining why I value a goal and choosing it deliberately, rather than hanging my hopes on a system that I hope might choose me.